The lines of white shirts, short-haired heads and braids with many colored bows stayed across the Red Square up to the tribunes. Yana was looking around and could see behind herself columns of people moving from the Okhotny Ryad as if somebody wrote straight lines on a sheet of paper; they were lower and lower up to the present-day State Department Store.

It was a square-page covered with writing. Phrases, words and letters were heard. Groups of children were seen, and she, Yana, was among them as one of thousand letters! From the right and the left sides and behind her the same children-letters were standing; they were small but very respectable. They were standing shoulder to shoulder. Yana could feel their warmth and breathing and knew they could feel the same things.

An unseen and inspired voice from castellated Kremlin wall was flying over the square:

"I'm a young pioneer of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics..." The square repeated it ringing and resounding echo. Scared doves were flying up and make circles over people's heads.

"I swear to live and study, so that I can become a worthy citizen of my socialist Homeland..."

Then a command sounded, "Put on your pioneer ties."

And the square miraculously began to blossom with scarlet fires of pioneer ties. In expectation of her turn to go out of the line and approach the young pioneer leader Misha with resolute step Yana nearly fainted with emotion. But when this moment came, and Misha twisted her neck with flame-colored and rustling silk, Yana suddenly realized that from this time on a different wonderful life should begin for her where there would be no place neither for Lyuska, nor for raids to Kolkhoz garden, nor for bad marks for arithmetic, nor for lie, nor for all kinds of foolish tales.

She swore. She would become worthy.

It came to pass that in a few days she decided to be baptized together with Lyuska's brother Vitya and make another the most important vow, not to Xenia's god but to God of the priest who came to baptize Vitya and who told Yana to make a vow to behave, obey her mom, not tell lies, study well, love her Homeland but first of all God and her neighbors, i.e. comrades as Yana understood. She loved God as he was though the priest's God was stricter than Xenia's.

At the end of the war it was announced that God not exactly existed and not exactly was opium for people as it had been considered before but he was something like a fairy from the film 'Cinderella' and a protector of truth and justice. You know that Fairy was not a simple fairy but Cinderella's cousin, and there was a magic country in the film looking like God's Kingdom where all wishes were coming true.

"The terrible Judge exists, and he is waiting.

He is not accessible for ringing gold.

He foreknows all thoughts and deeds..."

it meant God still remained in a fairy-tale dimension but he became a positive personage and our Soviet God. He helped to defeat Germans, saved in battles, sent bitter frosts to Russia to destroy manpower and military equipment of the enemy. Before God supposedly helped 'dark forces' that maliciously oppressed people to swindle and rob common working people but now God 're-educated himself' and came to our side.

In short, God was a fairy tale but this fairy tale became a good one. Churches became to open but very few of them remained whole, and tender-hearted priests in civilian attires visited towns and villages, consecrated houses, listened to confessions and gave communion to those who wished it, collecting written requests for the health and for the repose and baptizing children of war at their homes. It was done in a stealthy way, almost illegally, but it was done, and authorities shut their eyes to it. And once Lyuska, being puffed up with pride, informed Yana that tomorrow on Sunday a priest would come to their barracks, and everybody would pray that the war should finish, that nobody shouldn't be wounded and killed; he would exorcise devils from their barracks and then baptize children. She and Vitya would be baptised, Yasha and Svyeta too, and squinting Marina from the third barracks...

"And me?" Yana fainted.

"My mother said that your mother wouldn't allow because she was a Jew."

Yana rushed home in tears, making ready for hard fight but her mom unexpectedly said, "Your father is baptized. You are grown already; it's for you to decide."

She got a clean undershirt out of the commode, gave some money for a candle and a crucifix and wrote a confirmation for a priest that she didn't mind to performing 'baptismal ritual' of her daughter.

All children had godparents. As her godmother Yana called Fairy, her kindergarten teacher in an evacuation zone. But she didn't remember her name and named her Xenia. And she imagine granny Xenia in a white dress, in a wreath a flowers, how she flew to God but her face was young and girlish like Fairy's from the kindergarten, and in her hands she kept a magic stick and could make miracles as Cinderella's Fairy could.

During her baptism Yana amazed everyone reciting 'Our Father'.

Nobody told her that a pioneer shouldn't believe in God or that an Orthodox believer shouldn't join pioneers. Maybe, she was lucky but when she only once saw profiles of Lenin and Stalin on the first page of her ABC-book she realized that on the first page there should be the One Who created everything and Who was everywhere, everything and always.

It so happened that from the first steps of her life God, the Homeland and the Leader took right hierarchical places in her being.

She took a vow to God, her Homeland and the comrade Stalin. She would become worthy.

It was really an amazing life. Meetings, campfires, sport contests and pioneer camps caught up and carried the pioneer and later a Komsomol member Yana Sinegina. Somehow it came that she soon became an activist, a chairman of the council of the Young Pioneer unit, a Komsomol organizer and in the end an editor of the school wall newspaper 'The Eaglet'.

And before going to sleep she as usual prayed 'Our Father', for her Homeland, for Stalin and for her neighbors. God was in heaven, the Homeland and the comrade Stalin were on the earth, and that was all. Not God but earthly church was a taboo for her then. There dwelt malicious old women in black, and in general everything was incomprehensible there. It seemed that reading of Gogol's 'Viy' influenced her, though the author refuse it at the end of his life.

Somehow it came that from then on she was in full view of everybody, and it became improper for her to get three or four marks; she had to become a high achiever. And it was impossible not to defend the sportive honor of her school in relay races, 100-meter sprints and in jumps: she had to torture herself in a sports hall.

And it came that in this new, diverse, full of content and swift life she didn't have a free moment; she had to limit it by granite walls of strict regimen: lessons, sports and public work. She came home only to overnight and changed her clothes; she had launches at a school dining hall and studied at a public reading hall.

It seemed to her that it suited her mother and stepfather. By then the stepfather appeared already. Were those her best years? Maybe, it was so. She had no doubts, anxieties and agonizing fruitless thoughts but only action or energy of an oarsman who went with the current and was sure of rightness of a river, bringing him to his cherished goal. She was sure that she lived rightly, and so she was happy. She wrote articles, feuilletons, fables and stories from school life. Every year she got prizes for the best wall newspaper in the district and heard the words that had become an axiom 'an extraordinary talented girl, the pride of the school'. And she icily reproved boys who already began to keep their eyes on her; only friendship was possible between them! Leo Koshman in his narrow and greasy jacket and yellow fingers because of smoking seemed to her as coming down straight from Olympus.

"I'm from a district newspaper 'Flame'. We have decided to propose you to become our out-of-staff reporter; you will report the life of not only your own school but other Komsomol organizations, in general, perform tasks of the editorial board. Do you agree?"

"But she is overburdened even without it," the school manager Maria Antonovna exclaimed, "and in addition to it she studies in a senior class."

"I agree, Yana screamed in an altered voice, "dear Maria Antonovna, I will cope with it!"

An again Yana in the same cheerful and swift way shot through that life of hers.

The communist moral code was her sincere belief, agreeing with her conscience and with the Law inscribed in her heart, High thoughts, inner spiritual ascension, all people are good, the only thing is that they must be brought up, care for their needs and justice, moral purity, disapproval of her own and others' egoism, avarice, narrow-mindedness, unnecessary luxury - all of that agreed with her inner religiousness.

Very early did she understand that most of people were foolish sheep but authorities and intelligentsia. i.e. guards who kept them from consequences of original sin or 'vestiges of the past' and who are called to be a bridge between Heaven and folk mass 'to cultivate reason, kindness and eternal values'. Not without reason the word 'culture' originates from 'cult', i.e. service to Heaven.

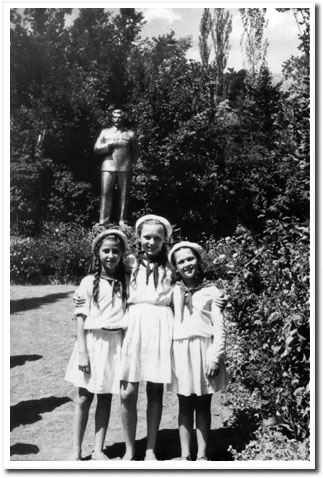

Her memory fixes moments and chaotic fragments of some lessons, meetings, conferences, school editorial board and trainings. She got to the summer of 1951 when she was prized with a voucher to pioneer camp Artek or sat on an overturned lifeboat; at her feet a see was splashing, the see was all in fiery sprays of the sun that was broken against the horizon. Nearby there was the brown-eyed little girl Madlen, a daughter of a French communist. With genuine interest she was questioning about the situation with communist in France but Madlen suddenly put her hand on her head and whispered diligently pronouncing Russian words.

"I have a boy in France, a boy, understand? Amour. I miss him, understand?

And here was another summer in prestart fever she was hanging around a stadium tribune; she wanted to mingle with the crowd of fans and run away.

She always shook before starts, before exams and first lines. It was fear before start.

"Partakers of 1000 meter race, go on your marks!"

With her peripheral vision Yana could see profiles of her rivals. "O God, if only she not came last of all! She has no right to let her school down. O Lord, help!" Her toes stuck into chalky start line and grew into the ground; every heat of her heart nailed them deeper and deeper like a hammer. It seemed that no power could pull her toes out of the red crushed bricks."O Lord, help!"

She didn't hear a shot of a starting gun but suddenly understood that she was running already, swifter and swifter. Her rivals were running behind her. Ahead the second turn was seen, and Yana knew that there she would weaken, and after the third turn a hell on earth would come. To her last breath she would swallow burning hot air, and pains in her side would become unbearable but she should bear everything. Then she found herself in the first group of five; it was a task assign by the trainer. Worse result was impossible, or else they wouldn't be sent to the regional contest.

All the school was looking at her. "O Lord, I can't let them down, you know!"

it was the last turn. Everything was as ever. Daggers stuck into her side, air burned her lungs, her rivals breathed to her back and couldn't catch up with her.

"Yana, Yana," she could hear yells from the tribunes like from a deadly abyss, and she ran along this abyss, though she should have fallen into it long ago, into desired cool immobility. She couldn't run but ran, and there was nobody ahead.

"I can't come in first," thought she or what left of her, "it can't be so. I'm dying. I don't care it."

She jumped over that deadly border, over 'I can't' and ran.

She came in first and showed the best hour in her life. She even managed to recover her breath and enjoy win laurels. But since that time she gave up sport, and there was left only her deep admiration for those people, for their deadly combat with themselves, and wonder: how can one bear such things for money?

"I thank you, Lord, for my wonderful war and post-war childhood and for wonderful fairy-tale films. Though being beautified and childishly naive like Christmas stories and saints' lives, they taught to be unselfish, selfless and courageous and warned against ruinous passions that were not proper for man's high status.

I thank the Lord for wonderful operas: "The Swan's Lake', 'The Nutcracker', 'Guilty Though Guiltless', 'An Optimistic tragedy' and 'The Blue Bird'. Once a month a trembling and big-nosed bus drove us to Moscow to some culture events, and that culture of the Soviet and golden age, that was originated from the word 'cult' and passed though censorship, was instead of sermons for us because it came from preaching; it was an attempt to clean God's image in man from piles of rubbish, dirt and madness. For her best qualities she was obliged to that censored culture, which in the conditions of thirst for religion was the 'milk' that was likely to save several generations from spiritual death.

Sifted out and forbidden performances, films and books, which she secretly searched for in her mother's and library's shelves, all those manuscripts and photocopies, passing from hand to hand, and viewing underground films didn't quench her thirst with the exception of Dostoyevsky, Bulgakov and Religious Revival of the Silver Age. They turned out to be short-lived, disturbing, depraving and bringing out the beast in people. In general, it was devilry.

I thank for kid lit books by Arkady Gaidar, Marshak and Boris Zhitkov, for 'The Young Guard', for fairy tales by Pushkin and Andersen published by vast amounts of copies as well as Leo Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, Lermontov, Pushkin. Of course, classic literature was also passed through censorship like Pushkin's 'Gabrieliade' but the author himself should have been much obliged for that censorship.

I thank for the Soviet musicians Richter, Oistrakh and Hilels and for concerts by Igor Moiseyev. After them she wanted to live purely and honestly, become better and create bright future.

That world was simplified, primitive and beautified (bloody showdowns took place even in that time). But we, little and grown-up children (the commandment 'you shall become as little children' was a feature of people with true Soviet upbringing) were diligently protected from storms, dirt, struggle for power, inconstancy, blood and passions, from all things that are called 'worldly life'.

Being children of from five to seventy five years old, we knew that somewhere there was another life: catastrophes, struggle for power, gold and a place in the sun, unemployment, misery, mafia and other horrors, found out something from forbidden books, scabrous and evil 'enlightening leaflets of the kind 'read and pass to others', from western broadcasting and foreign publications. As a rule, we were protected from the things that should be repented of according the Orthodox canons.

We were protected from evil and from those who stood up for freedom of evil.